In a day when art objects are considered part of an investor’s portfolio (especially for high net worth individuals acquiring assets of $20 to $30 million and above), over collecting can become an issue. Too much invested in art can mean too little placed in other financial assets, resulting in an unbalanced portfolio.

If this happens, some might call this collector is overenthusiastic. Others might term her or him obsessive or even a hoarder.

A research team at King’s College London is looking into these differences.

Ashley Keller, a PhD candidate researching hoarding at King’s College, believes there are certain characteristics that distinguish hoarding from collecting. The biggest difference is levels of organization: collectors engage in “ritualistic behavior around organizing their items,” she explains, “whereas with our hoarders we see a much more indiscriminate acquisition process, and this emphasis on organization just isn’t there.”

The second distinguishing feature is distress.

“Most of the collectors we see are enjoying their behavior even when they’re acquiring quite a bit… Whereas for hoarders, while they may enjoy getting the items and they may enjoy talking about an individual item, the overall behavior is very destructive and it’s very unpleasant for them.”

However, one of the most intriguing findings from the research on hoarders and collectors at King’s College was that collectors tend to have larger property sizes than hoarders. Keller says that there are two conflicting interpretations for this.

Now may be an Opportune Time to Sell Your Art

Jan 16, 2014 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

When I purchased early eighteenth century tea wares from a ship cargo seven years ago in Amsterdam, they cost much more than anyone would have predicted. As an absentee bidder, I didn’t know whom I was bidding against. When I enquired, I was told the individual was Russian.

More recently, I sold a late sixteenth/early seventeenth century Chinese lacquer box, not at the highest possible price that I hoped, but still a respectable one. The buyer, I believe, was Chinese. Other nationalities, too, are beginning to buy art in increasing numbers.

Some of what they are purchasing was originally their own and lost through colonization — the necessity to sell because of desperate times or due to being physically forced to give up their treasures. Other pieces currently being acquired by these individuals just entering the art market are newly made rather than old.

In an article in Spear’s Magazine last year by Ivan Lindsay, Steven Murphy, CEO of Christie’s International said, “Twenty-five per cent of our buyers last year were new to Christie’s…”

Who they may have been was clarified by the results of the Sotheby’s Old Masters Sale in London July 3, 2013. Top lots were purchased by Chinese, Russian and Indian nationals. All three countries are considered emerging economies compared to the United States.

The Art Market in a Muck

Nov 06, 2014 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

If buying a fake piece of art can happen to Steve Martin, the actor and clearly a high-profile individual, why can’t it happen to you and me?

According to many experts, 50% of the art on the market is fake. This gives us a moment for pause. One issue is whether high-net-worth individuals ($30 million and above) are really improving their overall asset positon by including art as a small percentage of their investment portfolios. Another is whether it is safe for the rest of us to be buying art at all. Or, yet another consideration, should we just not care and purchase what we can afford and like?

Hope Springs Eternal

Recently I purchased a blue and white Chinese plate said to be made around the year 1600. When I acquired it from a dealer located in a major capital city abroad I was already a bit suspicious. To me the blue coloration was off and the design on the large plate was less than traditional. Still, I needed it for an exhibit I was planning and wanted the plate to be as it was described—made around and about 1600. So, I talked with the dealer to discuss my concerns. I was told the color was not true in the photography and literally, “Not to worry.” Being more optimistic than prudent, in part since I had dealt with this dealer before and trusted him and his partner, I chose to buy the plate for the projected exhibit.

Read more at: http://www.hcplive.com/physicians-money-digest/columns/my-money-md/11-2014/The-Art-Market-in-a-Muck#sthash.Y6nuePQt.dpuf

Cubism Exposed

Dec 04, 2014 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

A new exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City displays Cubist art.

Science helps us understand why we see what we see.

Since cubist art reduces natural forms into the abstract, it has to be interpreted. As I walked through the new Cubist show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City this past Thanksgiving week, I noticed that I seemed to favor those paintings that I could decipher easily. The exhibition entitled, “Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection” runs through Feb. 15, 2015.

So, I got to thinking, am I the only one who prefers forms I readily understand rather than those I have to work to interpret? As it turns out, the answer is “no.” Others also lack energy for this kind of task.

We have researchers in Germany (Kuchinke, et. al.: “Pupillary Responses in Art Appreciation: Effects of Aesthetic Emotions”) to thank for this knowledge. They examined pupillary response to cubist art of varying degrees of complexity in their laboratory. In this way, standard pupil measurements could be taken while the art was observed. The pupil dilates and constricts not only to dark and light, but also when a viewer is interested in a work of art (dilates) or not (no response).

When the volunteers identified shapes that they recognized within the Cubist art, their pupils dilated indicating interest. These same paintings were also those most preferred in a questionnaire.

When the subjects could not process the representations, their pupils basically showed no change. This artwork was also less favored upon questioning. For example, in the above illustrations a) proved to be of more interest than c). It was also a) that had the most easily identifiable form within it.

Read more at: http://www.hcplive.com/physicians-money-digest/columns/my-money-md/12-2014/Cubism-Exposed#sthash.oe37hoDi.dpuf

Fakes in the Art Market: How a Dealer Turned a Lemon into Lemonade

Buying is easy; Returning—not So much

For me, this story is very strange. A dealer sold me a fake. (See my previous column, The Art Market in a Muck, for the backstory.) Then, he resisted taking it back. To put me further off from returning it, he cited his years of experience handling and selling Chinese porcelain as proof the piece must be authentic. For further ammunition, he threatened to take the case to BADA (the British Antiques Dealers Association) to discredit me. Lastly, he said that he would never sell to me again—

I’m not sure he had to worry about the latter, but it is duly noted.

So, there was tension between the dealer and myself regarding my wish to return the dish I purchased. The seller wanted me to retain it and he would keep my payment. I wanted him to take it back and make a refund. We were at loggerheads.

But there was one thing I knew for sure. If I didn’t send the piece back, my money would never be repaid. So, I took a chance. I completed the complicated paperwork and packaging to ship the porcelain back to London. Within, I included my own weapons. They were composed of the statements of 2 experts who wrote books on the particular kind of dish I was returning. In addition, I included scientific observations by a specialist who uses surface microscopy to determine fake from authentic Chinese porcelain. All the experts independently came to the conclusion that the porcelain was not authentic.

As an aside, when I told the dealer over the phone about the surface analysis, he completely discounted it, saying something to the effect that “one expert says one thing and another, another.”

Remaining civilized

The dealer did refund my money in parts after he received the package. Though I had bent over backwards to make my case for returning the piece, I hoped he would not be angry. In a small field like Chinese porcelain, it is best to avoid making enemies. Also, this merchant had sold me wonderful objects in the past. He probably just made a mistake.

So, when the microscopy specialist was in London giving a presentation, I took the opportunity to go to London to hear it and also to take him to the dealer. My purpose was to demonstrate scientific evidence to the dealer that his piece was not real.

Analytics trumps aesthetics

When I arrived with the specialist in tow at the dealer’s shop, the dish the dealer sold me was nowhere to be found. But, he had other items that he thought might be less than authentic. He brought out 2. Between them, one was genuine using the microscopy technique and the other wasn’t. The dealer was impressed. He saw that science can trump judgments made purely by the eye. He wanted my companion to stay and continue examining his porcelain (free of charge).

Gender and Art Appreciation: Sex Makes a Difference

Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder. Men and women generally are drawn to dissimilar styles of paintings. A man’s preference is on the left (illustration from Wikipedia) and a woman’s is on the right (illustration from Happy Painting).

In behavioral studies, men and women are known to rate the beauty of artistic and decorative stimuli in different ways. Although this tendency is recognized, the reason why is not. Recently, Camilo J. Cela-Conde and his colleagues began to explore the answer to this question. This is what they found.

During visual artistic appreciation, a particular area of the brain, the parietal lobe, was stimulated in both sexes. However, the sides of the brain that displayed activity in the 2 sexes were not the same. In females, it was on both sides and in men, it was primarily the right. The authors explained, “Our results showing an early activity of parietal areas for stimuli rated as beautiful in both sexes seem to indicate that the processing of spatial relations is crucial in the human appreciation of beauty. However … activity in the parietal regions is bilateral in the case of women but lateralized to the right hemisphere in the case of men.”

To reach their conclusion, the researchers studied 10 female and ten male neurobiology students. Their average age was 23.6 years. They had no earlier training or special interest in art. All were shown the same set of photographs of artistic paintings or natural objects that were divided into 5 clusters. There were 50 pictures each for the first 4: abstract, classic, impressionist, and postimpressionist art. The final group consisted of 200 photographs of landscapes, artifacts, urban scenes, and similar.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) was used to record brain activity and appropriate data analysis was applied. MEG is a method for detecting changes in magnetic fields produced by postsynaptic neuron activity with a time resolution of milliseconds. For more detail, please see the paper.

Why People Buy What They Know They Won't Use

My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

A collector friend of mine in her eighties said, “We have to get that goblet to complete the set.” Her passion, resolve and determination were evident in her voice. Her goal is to match antique glassware to complete a set, for example, 6 instead of 5 or 8 rather than 7.

As a fellow collector, this makes sense to me. I do the same, but with unmatched Chinese teapots meant to demonstrate different shapes and patterns over 2 centuries. Our shared passion is completion, whether it is of a pattern (my friend) or different prototypes of the same object over time (me).

Catherine Carey gives us insight into this force of human nature in the Journal of Economic Psychology. She discusses collecting for the purpose of set completion rather than financial gain or other reasons, though they are not mutually exclusive. For example, a set may be worth more in the secondary market than its parts individually.

What is new in Carey’s paper is that she constructs an economic model out of a pastime usually perceived in these terms. She explains the economic utility of collecting in sets.

By dictionary definition, economic utility is the ability of a good or service to satisfy the need or want of a consumer. Carey’s explanation is broader, “Utility maximization is indeed the seeking of satisfaction and the tradeoffs taken to enhance such pleasure.”

In more simplified terms, set collectors initially gather objects that have value to them as individual units. Later, as more parts are added and a set begins to take shape, single pieces are of less interest, but valued rather for the good they offer to make the set whole. In Carey’s words, “The social value may simply be the individual’s utility from owning the complete set ….or it could be a collecting community’s idea of the collection’s financial worth on the secondary market. In either case, set completion motivates collecting behavior.” The author goes on to say that the relevant literature suggests that this model represents a significant percentage of collectors. My experience is compatible with this.

Appreciating Art: Not All in the Brain

Jun 11, 2015 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

When viewing art, some museum-goers get that loving feeling. They like what they see and they see what they like. A few go so far as to have a religious experience of sorts and report sensations of euphoria. These perceptions, originating in the brain, aren’t all that is going on in a museum visitors’ body. The area below the neck is also engaged.

Psychologist Wolfgang Tschacher and colleagues from institutes in Switzerland and Germany recently demonstrated this to be true. They examined the physical responses of 373 museum visitors to the Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, in Switzerland. By using a specially made glove on the visitor’s right hand, their motion, heart rate, and skin conductance levels were determined wirelessly.

Sixty-five percent of the participants in the study were female. The average age of all was 47 years. Each subject spent on average of 28 minutes in the exhibit.

Skin conductance levels (SCL) measure the electrical current readings of the skin which vary with its moisture level. Differences are associated with emotion because the involuntary sympathetic nervous system responsible for the fight or flight response controls SCL. Thus, when someone is excited, activity in the sweat gland is increased which elevates skin resistance. This is recorded as a measure of emotional response.

An immediate post-visit customized computer questionnaire was used to evaluate responses to the 3 artworks where the participant lingered the longest (determined by the motion sensors in the glove). Responses to 3 artworks chosen in advance by the investigators were presented as well. Five areas of aesthetic appreciation were assessed.

“Aesthetic Quality”: Pleasing; beautiful; well done with respect to technique, composition, and content

“Surprise/Humor”: The work is considered as surprising; makes one laugh

“Negative Emotion”: The work conveys sadness, fear, anger

“Dominance”: The work is experienced as dominant, stimulating

“Curatorial Quality”: The work is well staged and hung, suitable in the context of other artworks

Using statistical measures, the researchers found that 3 of the 4 physiological measures used to determine biological responses to art in the museum showed significance.

Beautiful, high-quality artworks and surprising or humorous pieces were significantly associated with a higher heart rate variability.

Works of art perceived as dominant were significantly associated with a higher skin conductance variability.

Dominant art was also associated significantly with a decrease in heart rate.

Interestingly enough, only skin conductance absolute levels were unassociated with any parameter.

Tschacher and his colleagues were sparse in explaining any meaning this might have for their participants, though this wasn’t really necessary. Their major conclusion stands on its own: there are measurable physiological response to artworks in a museum. The authors sum this up by saying, “Our findings suggest that an idiosyncratically human property—finding aesthetic pleasure in viewing artistic artifacts—is linked to biological markers.” Our appreciation of art is not all in our heads!

The Delay That Satisfies: How to Be Happy by Not Buying Things You Don't Need

Jul 30, 2015 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

Lately, I’ve had two experiences that seem almost bizarre. I was attempting to buy decorative objects—high-end items from brick-and-mortar businesses that advertise on the Internet. With my initial rush of excitement upon seeing their photos, I even imagined what the pieces would look like in our home. But, because I couldn’t examine them in person, instead of purchasing outright, I asked the sellers questions. The merchants were slow to respond and therein lies my story.

My own reaction to this was, I thought, curious. In the intervening time between my wild enthusiasm about making the objects mine and when the sellers got back to me (days and days and days), I lost interest in the objects altogether. I feel I would have been happy if I purchased them outright, but I couldn’t because I had concerns that needed to be answered. As time went on and the dealer apparently thought I would hold my desire endlessly, I found I was content and didn’t need the pieces that I thought I did. This was in spite of the fact that I initially believed they would enhance my well-being. In the end, I was happy not purchasing what I supposed I wanted.

What in the world happened here?

My turn-about, I believe, is consistent with a Neuroeconomic phenomenon known as “temporal discounting.” It relates to decisions made under uncertainty. And, my decisions were certainly made under those conditions. Here is the neuroscience explanation:

When we desire something and it is available immediately, it is especially attractive. But, if we have to wait, it is less so. In cases where we have to wait, there has to be a payback for delaying the reward. In my case, had the same items been offered at a large discount after the 10- or 20-day interval it took to answer my questions, I might have been persuaded positively. Then, I may have purchased in spite of the wait. But, that didn’t happen. The dealer wanted the same price in spite of the fact that I had to postpone my buying decision. By the time I had enough information, my enthusiasm was all but dead.

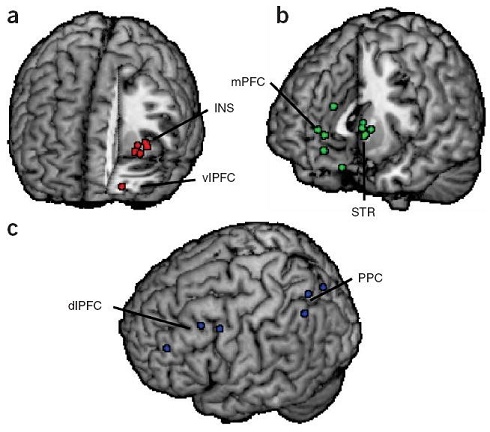

Brain regions implicated in decision making under uncertainty. Shown are locations of activation from selected functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of decision making under uncertainty. (a) Aversive stimuli, whether decision options that involve increased risk or punishments themselves, have frequently been shown to activate insular cortex (INS)33,52,53,58 and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC)61. (b) Unexpected rewards modulate activation of the striatum (STR)43,46,53,59,76, particularly its ventral aspect, as well as the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)43,53,61,76. (c) Executive control processes required for evaluation of uncertain choice options are supported by dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC)52,58 and posterior parietal cortex (PPC)33,34. Each circle indicates an activation focus from a single study. All locations are shown in the left hemisphere for ease of visualization.

From “Risky business: the neuroeconomics of decision making under uncertainty.”

Michael L Platt and Scott A HuettelNat Neurosci. 2008 Apr; 11(4): 398–403.

Published online 2008 Mar 26. doi: 10.1038/nn2062

In practical Neuroeconomic terms, temporal discounting relates to many areas of human decision making. For example, this is why it is necessary to give savers an incentive. Basically, they would rather spend their money than put it away for a rainy day. But, if they gain interest on their cash in the bank or in dividend producing blue chip stocks, they get reimbursed for their patience. The brain processes that produce temporal discounting are satisfied.

Of course, savers are putting away money for when they will need it—a very practical thing to do. On the other hand, I was buying something I desired but really didn’t need (nor does anyone else). But, in spite of this I still felt that pull of the immediate over the delayed.

Art: The Chinese Are Buying?

Sep 17, 2015 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

“Timing is everything when selling art.” This is what Geraldine Lenain said to me when I visited her in Shanghai, China while speaking at a conference there. Lenain was then international head of Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art for Christie’s Auction House in Shanghai and now is with their Paris office.

For me, at no time could her words be more potent. The recent sale of The Sowell Collection II of Chinese export art at Christie’s in New York City on Wednesday could be described as painful. Only 44% of the auction’s offerings sold. This was roughly half of what the Sowell Collection I sold for back in January at the same auction house in the identical city. Then, 74% of the Chinese export porcelains offered sold. The items in the two sales were from the same collector and not substantially different. What did change, I believe, was the willingness of the Chinese to buy back their heritage. I wrote about this phenomenon back in March, in a column entitled, “The Chinese are Buying and Americans Receive the Benefit.”

Today, there appears to be a shift and indicators point to the Chinese economics as the cause. The Chinese economy has virtually gone from boom to bust. This situation, of course, could influence any Chinese buyer and make her shy of spending her money on possessions she may want but really doesn’t need. That era may be over, at least temporally, for most Chinese. Though there are still bidders from China (I heard the auctioneer refer to them on the phone while listening in on this week’s sale), there likely are fewer that want to spend big sums of money.

Read more at: http://www.hcplive.com/physicians-money-digest/columns/my-money-md/09-2015/art-the-chinese-are-buying#sthash.Jb989X0d.dpuf

The Cyclical Rotation Effect: A Factor in the Art Market and the Stock Market

Oct 15, 2015 | My Money MD | Shirley Mueller, MD

My phone representative said, “He never takes down his hand.” This was my counter-bidder for Chinese export porcelain at the Marques dos Santos Leilões sale of Chinese export art Sept. 25 in Oporto, Portugal. Chinese export porcelain is porcelain made in China and exported to the West.

What was surprising was not that I was outbid, but the nationality of my opponent. He was not Chinese (this ethnic group been rabid in the auction market of late for all things Chinese). Rather, he was from India.

This competitor for the auctioned Chinese export porcelain lifted his arm and did not drop it when he wanted to make a purchase. Bidders in the room found this intimidating no doubt, but it was also intimidating to me as a phone bidder. I knew that if I desired a lot and this man did too, he wouldn’t stop until he won it. Of course, that could mean he paid too high a price, but perhaps no matter to a wealthy person whose anticipation of owning Chinese export made his pleasure center burn brightly.

Secondary bidders in the sale were evidently Brazilian and English with Chinese buyers scarcely to be found according to my phone representative. So, it is with art. When a country’s economy nosedives as it has in China, generally fewer art enthusiasts buy art.

The Chinese are Buying Back Their Heritage

Shirley M. Mueller

At the recent March 2015 auctions during Asian Week in New York City, I was feeling very lonely. My usual gang was gone. The attendees were virtually all Chinese.

New York City auction houses were humming during Asia Week in mid-March. The buzz, however, was not due to English being spoken as in the past. It was Mandarin and Cantonese that was producing the background din. The sale of Robert Hatfield Ellsworth engendered a mini temporary exodus from China and Taiwan to Manhattan.

Ellsworth was arguably the most prominent dealer of all things Chinese and Asian in the middle decades of the 20th century. He died in August 2014 at age 85. The remaining items from his 22-room home on Fifth Avenue in NYC were auctioned by Christie’s. The Chinese and Asian artifacts from other prominent collectors such as Julia and John Curtis were also being offered simultaneously. Sotheby’s, Bonham’s and Doyle’s, also auction houses in NYC, were on the bandwagon with their own Asian sales. This provided an opportunity for mainland Chinese and Taiwanese to come to the city and bring back what had been taken from their homeland more than 60 years earlier.

For example, the gray limestone figure in the first illustration was purchased originally from C.T. Loo in 1941 in NYC. Mr. Loo obtained this and objects like it in war-torn China and sold them to eager Americans and others who coveted objects from the East. Think of the Rockefellers and their collection at the Asia Society.

For sure, no one will be buying what the Asia Society Collection now owns. But, the possessions of deceased Ellsworth, a dealer, are fair play.